www.theoxfordscientist.com

- First Duty

- ... the dry cough, a lethal hate crime

- ... open letter to Premier Danielle Smith

- Trump Guilty on all 34 Felony Counts

- shooting of PM of Slovakia

- YouTube channel, launch

- Carlson, tuckered out

- ... Chinese New Year - 2024

- ... orange jesus sprouts sixth finger

- ... Wagner Group in Africa

- ... conduct unbecoming an MP

- Alberta, burning

- ... the Trump legacy

- Eric LaMont Gregory

- Wacko in Waco

- Pence, Christian last

- ... Putin indicted

- The Egyptian Secret

- Fox fiction

- The Open Skies Treaty

- derailed in Ohio

- close your Twitter account

- ... espionage-a-lago

- Highland Park

- Canada bans handguns and assault rifles

- ... apology, only a first step

- ... world wide auto surf

- Conklin to Buffalo

- Danielle Smith and Liz Truss

- An End to War

- Globe & Mail, blatant sophistry

- conservative press, a fitting epitaph

- Uvalde, explanation time

- ... Ukraine, a crime against humanity

- Open Letter to Justin Trudeau

- Queen Elizabeth II

- Moscow Mitch

- ... illiberal roadshow descends on Edmonton

- ... don't cry for Kenney, Alberta

- ... Edmonton, on the world stage

- ... advertise in Chinese & English

- ... missing in Edmonton

- Human Rights

- Facebook, bankrupt ethically & financially

- Pelosi rejects Jordan

- ... vaccine roulette

- ... a mask in time saves nine

- 9/11 + 17

- the Gregory military doctrine

- lying Rodgers, unsportsmanlike Brady, falter

- ... best free traffic list 2021

- 34% of Covid survivors - will not fully recover -

- Trump ... doing Putin's bidding

- Coronavirus, a perfect storm

- Biden/Harris, ... America, can breathe, again

- ... in the heat of the day

- 11 September 2021

- Donald J Trump - like father, like son

- Jim Jordan will resign, inevitably

- ... raise money for your group

- Paris - Sanguinary excess, again

- Mitch McConnell is no Alexander Hamilton

- What Trump knew 28 January 2020

- None Dare Call It Murder

- use of force, part 2

- Coronavirus, the second wave

- Click & Join 2021

- Coronavirus Pandemic, Part 2

- Coronavirus Pandemic

- Terror Returns to London Bridge

- use of force, part 1

- Ohio's trio of shame

- ... how to earn Bitcoin

- Kenney: Scheer nonsense, part 2

- the dark charisma of Donald Trump

- the three stooges

- Trump's base, 24% and dwindling

- Scheer Nonsense

- getting away with murder

- World Wide Auto Surf

- Beyond a reasonable doubt

- Mueller, Redactions & Twitter

- An All Alberta Solution

- Obama Attends Raptors Game

- Call for action on cannabis convictions

- John Bolton: beware the Trojan horse

- Mandel Clarifies MMR Stance

- People First - Dai for Whitemud mp4

- Notley, Mandel or Kenney

- Dai for Whitemud. Dai for Alberta

- To refine or not to refine

- Trump under subpoena

- Mandel vs Elections Alberta

- Individual 1 - Donald J Trump

- Is Mississippi Learning?

- Stand Back & Stand By

- Flynn Seeks Delay in Sentencing

- Roadmap to Trump's Impeachment

- Michael Cohen sentenced

- Trump Obstructing Justice

- Defense Secretary Resigns

- The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Hate Crimes are Increasing

- Trump announces Military Doctrine

- The Meeting, Trump Tower, June 9 2016

- 13 Angry White Male Senators

- Mean SOBs, Ryan & Jordan

- Trumpgate, a review of the facts

- Treason by the Dozens

- Terror on London Bridge

- Anti-Trump Ryan as Speaker, doubtful

- Haiti - shameful Red Cross 40% admin costs

- Deadly Bastille Day in Nice

- Special Powers

- Brussels - revenge attack

- Gregory's forte

- America First

- Brexit triumphs in UK referendum

- Ali

- Guns, Obama, the NRA & the Cleric

- Gorsuch & Brown v Board of Education

- The Generosity of America

- To Protect and To Serve

- Where is Alma Del Real?

- The Islamic World - a primer for policy makers

- The Lists - The Missing and Unsolved Homicides

- Michiana Murders

- Clinton

- Kings, Emperors & John Boehner

- Donnelly - the constant campaigner

- Kevin McCarthy

- Alberta Party

- Selections from The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Malaysian Airlines Flight 370

- Ukraine - the Putin Doctrine

- Twilight

- Principles

- Bridge-gate: a closer look at Christie's staff

- Mandela

- Liangjun Wang

- Rethinking Syria

- about Chechnya

- Rethinking the War on Terror

- Tepid waters

- Linkage Blindness

- None Dare Call it Treason

- Emancipation

- Power

- Newtown - a cry for help

- Quarantine

- 11 September

- Hidden Crimes, Hidden Victims

- Cry, My Beloved Country

- Cruel Winds of October

- Doctrine

- Fed Video

- Under Seige

- Labor Day

- Destiny of America

- McEwen

- Rampage

- Threats

- GSK

- McEwen

- Condoleezza's watch

- Danger

- B R I C S

- Israel

- Huckabee

- Evidence

- Ties that Bind

- Sarajevo / Rwanda

- Violence

- Baby Safety

- MLK

- Libya

- Franklin

- Principles

- Fox 45

- America Wins Nobel Peace Prize

- Celina

- Middletown

- Arms Race

- Egypt

- Dollar

- 3 July

- $6 Trillion

- Jefferson and Adams

- 4th

- Libya

- Fening

- Abe

- Housing for Haiti

- Palin on Haiti

- ' ... an innocent man'

- Oil in the Gulf

- ... a wider regional conflict

- the demise of General McChrystal

- ... and to the republic

- BP and the Precautionary Principle

- Making Sense of Fort Hood

- Air Quality

- Un largo crepúsculo Lucha

- Israel

- Policy

- Home

- Casa

- un tambor diferente

- The Oxford Years

- Defense

- The Secret Hold

- INS will cease to exist

- ABC Toledo

- the grapes of wrath

- H1N1 Fluenza

- Tantamount to Treason

- MKL 4th speech

- Trans Dip

- Trump Rescinds DACA

- Rethinkin Syria

- Oxfam, IRC and other NPR Darlings

- Top Nine Articles for March 2015

- The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Where is Alma Del Real?

- Alma Del Real

- 11 September

- A Measure of Philanthropic Success

- Tantamount to Treason

- South Carolina

- Double Crossed by Double Standards

- Call for photo radar cash grab inquiry

- Remembrance Day 2015

- Trudeau victory portends

- Blair Speech to Congress 2003

- Justin Trudeau, Tony Blair & Marijuana

- Trump, Harper, Ambrose & Ryan

- Saudi Arabia vs Iran

- The Islamic World ... the basics

- 2020 Presidential Candidate Releases Book

- Mississauga house explosion

- Reset: Driving Black in America

- Giuliani, shut up, stop name calling & prepare to govern

- Stop the Madness in Aleppo & Mosul

- Drain The Swamp

- Unpresidented

- Trump & the CIA, the high priest of false security

- The Hour of Maximum Danger

- Quebec, Queens U, Charleston & Trump

- Paul Ryan, Steve King, Trumpcare & Babies

- Harvey wreaks havoc

- VPN, don't surf without it

- Anju Sharma, the right choice for Edmonton-Mill Woods

- Adlandpro

- Trump's Iranian ties

- Brianna Keilar CNN - the big lie

- ... best free manual surf list 2021

- the Gregory military doctrine

- theOxfordscientist.com now on Tik Tok

- Chopin

- in the Course of human events

- 37 countries ban felon Trump

- un Plat qui se Mange Froid

- Trump shot at rally by 20-year-old

The American Experiment

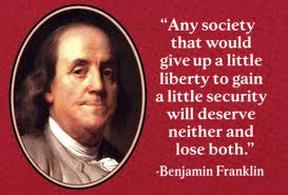

Reclaiming Benjamin Franklin's Promised Republic

“The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people; a change in their religious sentiments, their duties and obligations.

This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments and affections of the people, was the real American Revolution.”

John Adams

When the American Constitution was being signed at the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin remarked that he had often wondered whether the rays of the sun painted in the chair of the president of the convention signified a sunrise or sunset for the new country. According to James Madison, Franklin expressed his satisfaction that “now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.”

The Constitutional Convention was an extraordinary experiment, an attempt to determine, as Alexander Hamilton put it in Federalist No. 1, “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.” This is the challenge that today confronts the newly emerging democracies.

If the American experiment may be regarded as successful, if it is a model to be emulated, the reason must be found in the causes of the American Revolution. “The Revolution was effected before the war commenced,” John Adams observed. “The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people; a change in their religious sentiments, their duties and obligations. This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments and affections of the people, was the real American Revolution.”

Of all these changes, perhaps the most important was what historian Daniel Boorstin has called “the courage to doubt,” which was exemplified by Benjamin Franklin. Near death, Franklin was asked his opinion about a religious question. He expressed an opinion, but added that “it is a question that I do not dogmatise upon, having never studied it, and think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an opportunity of knowing the truth with less trouble.” Franklin was not troubled by living in a state of uncertainty regarding a question for which he had no good evidence one way or the other. Since a decision was not required, he was content to wait until better evidence became available.

The United States was built on this foundation of healthy doubt, which is expressed in American institutions. Indeed, the peaceful transfer of power depends on it. In a democracy, the minority cedes power to the majority on the assumption that the majority has a better claim to be in the right. The minority does not conclude that it must

be wrong; rather, it acknowledges, in effect, that it might be wrong. Just as important, the majority makes the same assumption, for otherwise it would not allow itself to be turned out of power merely for losing an election.

THE SPIRIT OF HUMILITY

Stanley Kober