www.theoxfordscientist.com

- First Duty

- ... the dry cough, a lethal hate crime

- ... open letter to Premier Danielle Smith

- Trump Guilty on all 34 Felony Counts

- shooting of PM of Slovakia

- YouTube channel, launch

- Carlson, tuckered out

- ... Chinese New Year - 2024

- ... orange jesus sprouts sixth finger

- ... Wagner Group in Africa

- ... conduct unbecoming an MP

- Alberta, burning

- ... the Trump legacy

- Eric LaMont Gregory

- Wacko in Waco

- Pence, Christian last

- ... Putin indicted

- The Egyptian Secret

- Fox fiction

- The Open Skies Treaty

- derailed in Ohio

- close your Twitter account

- ... espionage-a-lago

- Highland Park

- Canada bans handguns and assault rifles

- ... apology, only a first step

- ... world wide auto surf

- Conklin to Buffalo

- Danielle Smith and Liz Truss

- An End to War

- Globe & Mail, blatant sophistry

- conservative press, a fitting epitaph

- Uvalde, explanation time

- ... Ukraine, a crime against humanity

- Open Letter to Justin Trudeau

- Queen Elizabeth II

- Moscow Mitch

- ... illiberal roadshow descends on Edmonton

- ... don't cry for Kenney, Alberta

- ... Edmonton, on the world stage

- ... advertise in Chinese & English

- ... missing in Edmonton

- Human Rights

- Facebook, bankrupt ethically & financially

- Pelosi rejects Jordan

- ... vaccine roulette

- ... a mask in time saves nine

- 9/11 + 17

- the Gregory military doctrine

- lying Rodgers, unsportsmanlike Brady, falter

- ... best free traffic list 2021

- 34% of Covid survivors - will not fully recover -

- Trump ... doing Putin's bidding

- Coronavirus, a perfect storm

- Biden/Harris, ... America, can breathe, again

- ... in the heat of the day

- 11 September 2021

- Donald J Trump - like father, like son

- Jim Jordan will resign, inevitably

- ... raise money for your group

- Paris - Sanguinary excess, again

- Mitch McConnell is no Alexander Hamilton

- What Trump knew 28 January 2020

- None Dare Call It Murder

- use of force, part 2

- Coronavirus, the second wave

- Click & Join 2021

- Coronavirus Pandemic, Part 2

- Coronavirus Pandemic

- Terror Returns to London Bridge

- use of force, part 1

- Ohio's trio of shame

- ... how to earn Bitcoin

- Kenney: Scheer nonsense, part 2

- the dark charisma of Donald Trump

- the three stooges

- Trump's base, 24% and dwindling

- Scheer Nonsense

- getting away with murder

- World Wide Auto Surf

- Beyond a reasonable doubt

- Mueller, Redactions & Twitter

- An All Alberta Solution

- Obama Attends Raptors Game

- Call for action on cannabis convictions

- John Bolton: beware the Trojan horse

- Mandel Clarifies MMR Stance

- People First - Dai for Whitemud mp4

- Notley, Mandel or Kenney

- Dai for Whitemud. Dai for Alberta

- To refine or not to refine

- Trump under subpoena

- Mandel vs Elections Alberta

- Individual 1 - Donald J Trump

- Is Mississippi Learning?

- Stand Back & Stand By

- Flynn Seeks Delay in Sentencing

- Roadmap to Trump's Impeachment

- Michael Cohen sentenced

- Trump Obstructing Justice

- Defense Secretary Resigns

- The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Hate Crimes are Increasing

- Trump announces Military Doctrine

- The Meeting, Trump Tower, June 9 2016

- 13 Angry White Male Senators

- Mean SOBs, Ryan & Jordan

- Trumpgate, a review of the facts

- Treason by the Dozens

- Terror on London Bridge

- Anti-Trump Ryan as Speaker, doubtful

- Haiti - shameful Red Cross 40% admin costs

- Deadly Bastille Day in Nice

- Special Powers

- Brussels - revenge attack

- Gregory's forte

- America First

- Brexit triumphs in UK referendum

- Ali

- Guns, Obama, the NRA & the Cleric

- Gorsuch & Brown v Board of Education

- The Generosity of America

- To Protect and To Serve

- Where is Alma Del Real?

- The Islamic World - a primer for policy makers

- The Lists - The Missing and Unsolved Homicides

- Michiana Murders

- Clinton

- Kings, Emperors & John Boehner

- Donnelly - the constant campaigner

- Kevin McCarthy

- Alberta Party

- Selections from The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Malaysian Airlines Flight 370

- Ukraine - the Putin Doctrine

- Twilight

- Principles

- Bridge-gate: a closer look at Christie's staff

- Mandela

- Liangjun Wang

- Rethinking Syria

- about Chechnya

- Rethinking the War on Terror

- Tepid waters

- Linkage Blindness

- None Dare Call it Treason

- Emancipation

- Power

- Newtown - a cry for help

- Quarantine

- 11 September

- Hidden Crimes, Hidden Victims

- Cry, My Beloved Country

- Cruel Winds of October

- Doctrine

- Fed Video

- Under Seige

- Labor Day

- Destiny of America

- McEwen

- Rampage

- Threats

- GSK

- McEwen

- Condoleezza's watch

- Danger

- B R I C S

- Israel

- Huckabee

- Evidence

- Ties that Bind

- Sarajevo / Rwanda

- Violence

- Baby Safety

- MLK

- Libya

- Franklin

- Principles

- Fox 45

- America Wins Nobel Peace Prize

- Celina

- Middletown

- Arms Race

- Egypt

- Dollar

- 3 July

- $6 Trillion

- Jefferson and Adams

- 4th

- Libya

- Fening

- Abe

- Housing for Haiti

- Palin on Haiti

- ' ... an innocent man'

- Oil in the Gulf

- ... a wider regional conflict

- the demise of General McChrystal

- ... and to the republic

- BP and the Precautionary Principle

- Making Sense of Fort Hood

- Air Quality

- Un largo crepúsculo Lucha

- Israel

- Policy

- Home

- Casa

- un tambor diferente

- The Oxford Years

- Defense

- The Secret Hold

- INS will cease to exist

- ABC Toledo

- the grapes of wrath

- H1N1 Fluenza

- Tantamount to Treason

- MKL 4th speech

- Trans Dip

- Trump Rescinds DACA

- Rethinkin Syria

- Oxfam, IRC and other NPR Darlings

- Top Nine Articles for March 2015

- The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Where is Alma Del Real?

- Alma Del Real

- 11 September

- A Measure of Philanthropic Success

- Tantamount to Treason

- South Carolina

- Double Crossed by Double Standards

- Call for photo radar cash grab inquiry

- Remembrance Day 2015

- Trudeau victory portends

- Blair Speech to Congress 2003

- Justin Trudeau, Tony Blair & Marijuana

- Trump, Harper, Ambrose & Ryan

- Saudi Arabia vs Iran

- The Islamic World ... the basics

- 2020 Presidential Candidate Releases Book

- Mississauga house explosion

- Reset: Driving Black in America

- Giuliani, shut up, stop name calling & prepare to govern

- Stop the Madness in Aleppo & Mosul

- Drain The Swamp

- Unpresidented

- Trump & the CIA, the high priest of false security

- The Hour of Maximum Danger

- Quebec, Queens U, Charleston & Trump

- Paul Ryan, Steve King, Trumpcare & Babies

- Harvey wreaks havoc

- VPN, don't surf without it

- Anju Sharma, the right choice for Edmonton-Mill Woods

- Adlandpro

- Trump's Iranian ties

- Brianna Keilar CNN - the big lie

- ... best free manual surf list 2021

- the Gregory military doctrine

- theOxfordscientist.com now on Tik Tok

- Chopin

- in the Course of human events

- 37 countries ban felon Trump

- un Plat qui se Mange Froid

- Trump shot at rally by 20-year-old

... Missing in Edmonton

E LaMont Gregory MSc Oxon

E LaMont Gregory MSc Oxon

... the 2021 annual search of river valley included a search for a missing woman

Two recent missing persons cases in Edmonton, one concerning an 11-year-old girl,

located within a few days unharmed, the other a 21-year-old woman, also found

within a few days, but sadly, decease.

Both fit the ubiquitous criteria for police action in missing persons cases,

that of being - out of character for this individual - have renewed interest

in the operation of the Edmonton Police Service's - Missing Persons Unit.

The renewed interest, however, must be viewed in light of a multitude of unresolved

Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) cases, in the area,

and a recent highly controversial appointment by the MMIWG secretariat.

located within a few days unharmed, the other a 21-year-old woman, also found

within a few days, but sadly, decease.

Both fit the ubiquitous criteria for police action in missing persons cases,

that of being - out of character for this individual - have renewed interest

in the operation of the Edmonton Police Service's - Missing Persons Unit.

The renewed interest, however, must be viewed in light of a multitude of unresolved

Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) cases, in the area,

and a recent highly controversial appointment by the MMIWG secretariat.

... training, experience, data, talent & resources

In a training colloquium for federal missing persons investigators and administrators, the head of a national missing persons agency suggested that there were five ingredients necessary for a missing persons unit to be effective; namely, training, experience, data, talent, and resources.

In a nutshell, training and experience instill the necessary talents into the individual investigators and the missing persons unit, to allow investigators and administrators to apply the relevant data, and resources to the successful resolution of a missing persons case.

It cannot be overstated how important the prompt and proper application of one of the cardinal resources is, notably in the initial phase of a missing persons case, and that is, proper classification.

Between 70,000 and 80,000 people are reported missing to the police in Canada each year, the RCMP website states, "While most are found within seven days, missing persons cases can be extremely stressful for family and loved ones" - https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/missing-persons -.

"Currently, the Edmonton Police Service receives approximately 1500 reports of missing persons per year," according to their website - https://www.edmontonpolice.ca/CrimeFiles/MissingPersons -.

Each missing person report is classified into one of several categories.

In broad and general terms, missing persons are classified by investigators into one of several probable cause options i.e., accidents, wandered off or lost, runaway, unknown, and foul-play suspected, respectively.

The category runaway is usually reserved for those under the age of 18.

Missing persons classified as victims of accidents, include such circumstances as being swallowed up by an avalanche on a ski trip, or drowning in a boating mishap. Whereas, those classified as wandered off or lost, describe instances where an individual in a confused state leaves home, a hospital or other care facility, or becomes disoriented in the mountains, on a moor, or in the deep woods while hiking.

Unknown, is police code for instances where they have no record on the missing person, or alternatively, insufficient background information to categorize the missing person under any of the other probable cause options.

If, the initial, or a subsequent change of circumstances should come to the attention of a missing persons investigator that suggests foul-play is suspected, that is, the missing person is in danger and/or the circumstances of the missing person case is crime related, the priority and urgency of the case is also changed.

In a foul-play suspected missing persons case, the full spectrum of human and material resources can be assigned in a concentrated effort to ensure the safe return of a missing person.

Once a report is received by a missing persons unit, it is entered into the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) electronic database, which can be accessed by law enforcement agencies nationwide, to document and track missing persons cases. The CPIC acts as a clearinghouse of crime data and is located at RCMP Headquarters in Ottawa.

In addition, and again, depending on the classification of the missing persons case, the information would be entered into the Alzheimer Wandering Registry (AWR) when appropriate, and in cases of other medical vulnerabilities, the Vulnerable Person Registry (VPR). Cases involving Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MIWG) are reported, classified and entered into the appropriate registries, as such.

... missing persons is a labor intensive, machine-assisted operation

Let's take the sundry details we have covered so far, and see what additional information we can glean from it.

The Missing Persons Unit states that it receives 1,500 reports of missing persons a year, we will assume in our initial analysis that it takes a member of the unit one hour to take each missing persons report.

For the sake of our initial analysis, we will also assume that there is no travel time or costs involved, that is, in each and every case the person making the missing persons report does so by arriving at the unit's offices. We can, of course, make corrections to these assumptions later.

1,500 reports, each taking one hour to document, will involve an investment of 1,500 hours of the unit's personnel time.

We have also established that once received, the missing persons reports are then entered into various electronic databases, such as, the CPIC, AWR, VPR, and MMIWG, among others.

We will assume, in our initial analysis, that it takes one hour to enter each of the 1,500 reports into one or more electronic databases.

The missing persons unit expends 1,500 hours in receiving and another 1,500 hours in getting the missing persons reports into the electronic databases, a total of 3,000 hours.

For the sake of simplification, we will assume that one full-time sufficiently trained and experienced constable is responsible for both receiving and entering the data.

Our constable works five days a week, eight hours a day, and is paid for 40 hours a week, and receives a two-week vacation, and therefore, works 50 weeks a year.

The Canadian workplace affords each constable one hour a day for a meal and two 15-minutes tea or coffee breaks, duly earned given the stress factor in relation to working in a missing persons unit, in a busy metropolitan area, located on one of the tributaries of the murder trail.

We then have 6 and a half hours a day, and 32 and a half hours a week, our constable is actually available to receive and enter missing person data into the databases. 32 and a half hours a week, and 50 weeks, equals a total of 1625 hours a year.

In our example, there are 3,000 hours of work to be done, therefore, 3,000 hours of work, divided by 1,625 hours a year for one full-time constable to do the work, means that it would take our constable more that one year and 10 months, working full time to put in 3,000 hours to do the work.

Now, just to reiterate, 1,500 missing persons reports are received by the Edmonton Police Service a year, 1,500 divided by 365 days a year equates to four reports a day. In our example, each missing person case initially involves two hours in data collection and entry, so our four reports require eight hours work per day.

In this example, our constable has six and a half hours available a day, and eight hours of work to do. And basically, on the fourth day of the work week, one new case can be processed, because by the fourth day there is a backlog of three cases that have accumulated.

Again, we will assume that our constable is sufficiently trained and experienced to do both jobs, and just considering that to enter data into the CPIC database requires access to the database management system (DBMS) which controls it, we can assume that our constable is not at an entry-level pay grade.

And, we will delve into this aspect of the missing persons unit, as we introduce more facts about its actual operations, in the second and third part of this series. We will delve into it.

At this juncture, suffice it to say, that missing persons as conducted by the Edmonton Police Service, is a labor intensive, machine-assisted operation.

The Missing Persons Unit states that it receives 1,500 reports of missing persons a year, we will assume in our initial analysis that it takes a member of the unit one hour to take each missing persons report.

For the sake of our initial analysis, we will also assume that there is no travel time or costs involved, that is, in each and every case the person making the missing persons report does so by arriving at the unit's offices. We can, of course, make corrections to these assumptions later.

1,500 reports, each taking one hour to document, will involve an investment of 1,500 hours of the unit's personnel time.

We have also established that once received, the missing persons reports are then entered into various electronic databases, such as, the CPIC, AWR, VPR, and MMIWG, among others.

We will assume, in our initial analysis, that it takes one hour to enter each of the 1,500 reports into one or more electronic databases.

The missing persons unit expends 1,500 hours in receiving and another 1,500 hours in getting the missing persons reports into the electronic databases, a total of 3,000 hours.

For the sake of simplification, we will assume that one full-time sufficiently trained and experienced constable is responsible for both receiving and entering the data.

Our constable works five days a week, eight hours a day, and is paid for 40 hours a week, and receives a two-week vacation, and therefore, works 50 weeks a year.

The Canadian workplace affords each constable one hour a day for a meal and two 15-minutes tea or coffee breaks, duly earned given the stress factor in relation to working in a missing persons unit, in a busy metropolitan area, located on one of the tributaries of the murder trail.

We then have 6 and a half hours a day, and 32 and a half hours a week, our constable is actually available to receive and enter missing person data into the databases. 32 and a half hours a week, and 50 weeks, equals a total of 1625 hours a year.

In our example, there are 3,000 hours of work to be done, therefore, 3,000 hours of work, divided by 1,625 hours a year for one full-time constable to do the work, means that it would take our constable more that one year and 10 months, working full time to put in 3,000 hours to do the work.

Now, just to reiterate, 1,500 missing persons reports are received by the Edmonton Police Service a year, 1,500 divided by 365 days a year equates to four reports a day. In our example, each missing person case initially involves two hours in data collection and entry, so our four reports require eight hours work per day.

In this example, our constable has six and a half hours available a day, and eight hours of work to do. And basically, on the fourth day of the work week, one new case can be processed, because by the fourth day there is a backlog of three cases that have accumulated.

Again, we will assume that our constable is sufficiently trained and experienced to do both jobs, and just considering that to enter data into the CPIC database requires access to the database management system (DBMS) which controls it, we can assume that our constable is not at an entry-level pay grade.

And, we will delve into this aspect of the missing persons unit, as we introduce more facts about its actual operations, in the second and third part of this series. We will delve into it.

At this juncture, suffice it to say, that missing persons as conducted by the Edmonton Police Service, is a labor intensive, machine-assisted operation.

... a Real case in fact

- introduction -

- introduction -

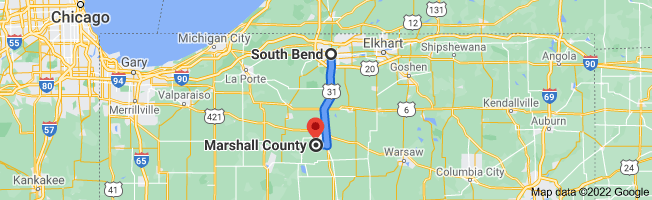

In 2015, the city of South Bend, Indiana, the location of Notre Dame University, in both social, political, and in terms of unresolved missing females, was very much like Edmonton, Alberta.

Pete Buttigieg, the 32nd Mayor of South Bend, was like the 35th Mayor of Edmonton, Don Iveson, a train wreck.

The chief executive of the state of Indiana was Mike Pence, and Alberta had Rachel Notley, and now Jason Kenney.

Alma del Real, the subject of our case study, went to a dance club with friends on Saturday night the 11th of April 2015. A male who had been at the club that night told authorities that he had driven the subject home at about 2am, in the wee hours of the morning of Sunday the 12th of April. The subject was never seen alive again.

The mother, after calling her daughter's friends, and receiving no information as to her daughter's whereabouts, notified the South Bend police.

The newspapers the next few days were filled with fantastic stories e.g., the disappearance might be linked to local gang activity; specific gangs were mentioned, and other media outlets suggested that she might have been ensnarled by the cartels. The police reacted by triggering the involvement of the gang taskforce, and even bigger guns who deal with organized crime. Large groups of volunteers were organized to scour the river banks, parks, bridal paths, etc., and etc.

On the third day of this frantic activity, this author contacted a high-ranking member of the investigating team to ask one straightforward question, "... are you using cell tower information to corroborate the whereabouts of all those who were at the club that night, especially those who had contact with the subject?" "That", the officer replied, "would come under the category of police business."

"Then", this author retorted, "allow me to rephrase, the use of cell tower information, could be used to corroborate ... ".

Police investigations, if anything else, are filled with discretions and subtleties.

What the high-ranking officer was alluding to by the phrase, police business, was the concept of 'guilty knowledge information (GKI)'. Guilty knowledge information, is a fact, or a set of facts (information) that is known only to the person responsible, and the police. Naturally, 'known only to' includes anyone with whom the person responsible, or the police, share the guilty knowledge information.

Guilty knowledge information is also used by investigators to identify false confessions, which are not infrequent, especially in highly publicized cases. Law enforcement behavioral scientists have also suggested that false confessions could be used by investigators to construct their null hypothesis scenario, given that the null hypothesis is the scientific basis upon which presumption of innocence under law, rests.

Was the statement suggesting that that would come under the category of police business, proper?.

Daily, during this period, members of the South Bend Police and the South Bend municipal administration were in print and on broadcast media exhorting the public that this was just the kind of case that could be resolved, if only, members of the public would come forward with pertinent information.

The criminology literature has analyzed a wealth of data concerned with community/police relations. That literature confirms that community policing has had a positive impact on those relations, and such factors as unsolved murders in certain communities bear a direct relationship to the pre-emptive murder rate in those communities.

But to a large extent, the criminology textbooks and journal literature document how policing policies and practices have had a chilling effect on members of the public, especially from racialized communities assisting the police with their inquiries.

At the extremes of poor community/police relations, residents expressed a greater fear of interaction with the police, than with the criminal element.

Naturally, one might think that the bulk of this research work is centered on cities like, Ferguson, Missouri, or Minneapolis, Minnesota, but and although those cities feature in the criminology literature, there is now substantial work ongoing concerning community/police relations, and the chilling effect policing policies and practices have had in two Canadian cities, Toronto, Ontario, and Edmonton, Alberta.

The most recent work concerning Toronto, relates to a massive series of raids and sweeps of marijuana cafes, involving hundreds of establishments and several hundred individual arrests, in Toronto, after the parliament had legalized marijuana, but just several weeks before the law actually took effect. The head of Toronto Police Services, is quoted as stating that the raids and arrests were 'to let the people of Toronto know, just who was in charge'. Be that as it may, professional scientific criminologists are concerned with the chilling effect, both acute and chronic, those raids and arrests have had on police/community relations.

The subject being investigated, documented, analyzed and reported by academic as well as professional criminologists in regards to the Edmonton Police Services' relations with the community, evolves around a decades-long deliberate policing policy and enforcement practices that manipulated crime solution rates by targeting racialized communities with an oversized and overactive police marijuana squad.

What the police called responding to public pressure to prosecute the perpetrators of the evil, but for the most part, minor use of marijuana, in reality the pressure was not emanating from the public largely (few parents sought to criminalize their children), but from an evangelizing high racialized community resentment driven local press establishment.

And, successive Edmonton Police Service administrations, including McFee as only the latest example, adopted what criminologists describe as 'noble cause corruption', that is, police policies and practices that encourages the police to blind themselves to their own inappropriate conduct, and to perceive that conduct as legitimate in the belief that they are pursuing an important public interest (5).

Facts, are indeed, stubborn things.

In addition, the scientific study of victimology, the branch of criminology concerned with such relationships as the interactions between victims and the criminal justice system, has had to incorporate the reality of the criminal justice system through prosecutorial-biased policing practices being the perpetrator of crimes, and therefore the creator of victims.

Equal protection under law, cannot and does not exist, unless there is equal enforcement of the law. It is the role of the courts to fetter out prosecutorial bias in policing.

And for decades, spanning successive mayoral and police administrations, there existed an utter lack of the slightest notion of judicial accountability, that is, an utter abrogation of the responsibility to eliminate prosecutorial bias, on the one hand, and a lack of judicial oversight, review and supervision of a succession of judges who failed to eliminate prosecutorial bias, on the other.

In other words, there was no judicial accountability, which allowed a vicious race-based police practice to victimize, largely youth from racialized communities, at will.

There is enough information presented here, for the surrogate provincial police of Alberta, the RCMP, to launch a major investigation into these matters, but first, the RCMP would have to purge from their ranks, members of their force that worked for the Edmonton Police Service, and whose sterling arrest records and high crime solution rates featured in their being employed by the RCMP.

Simultaneously, a United Nations Special Rapporteur should be established to investigate Iveson, Mandel and the other previous mayors, the current, Dale McFee, and the last several heads of the Edmonton Police Service, such as Rod Knecht, as well as, current and past judges who without considering prosecutorial bias passed judgement on thousands, largely from racialized communities, and the supervisors of judges, who acquiesced in this travesty, to prepare a case against them jointly and severely before the International Court. And the scale of the victimization, warrants such.

The problem lies in public administration, it began there, it was perpetuated there through the several municipal and police administrations, and the courts, and it will be remedied by public administration, whether it be local, national, or international.

Returning to our case study, there was one group this author could assume reliably, would be communicating with municipal chiefs of police, and county sheriffs on a regular basis, and that is, other municipal chiefs of police and county sheriffs.

This author held conversations with a number of the chiefs and sheriffs in the surrounding area, first relaying the information concerning the use of the cellphone towers discussed with the South Bend police, but never asking any one of the chiefs or sheriffs to communicate with the South Bend Police.

After the promised no more than 2 minutes of the executive's time expired, each and every one of the chiefs and sheriffs, often in explicit and graphic terms, explained that each of them had a catalogue of unresolved missing and murdered female cases, and that this was true for all the police chiefs and sheriffs in the whole of the Michiana area.

Contemporaneous to these discussions with the chiefs and sheriffs, this author recorded the following statement.

"It is high time for Governor Pence, the attorney general and the state police (with the FBI involved for investigatory assistance) to form a task force to investigate the alarming numbers of unsolved female homicides and unresolved missing persons cases in the Michiana area, within the Michiana cluster." - https://www.theoxfordscientist.com/where-is-alma-del-real.html -

Six weeks, over a thousand of hours after Alma del Real left the dance club, South Bend Police obtained a court order to examine the cellphone records of the individual that claimed to have driven her home at 2am in the early hours of the 12th of April .

After police discovered that the individual that said he drove the subject to her South Bend home at 2am,

had actually made a cellphone call, picked up by a tower some 30 miles south in rural Marshall County,

the individual then led the police to a culvert near highway 31, where the subject's body was found,

nearly six weeks to the day after she was last seen alive at a dance club in South Bend on a Saturday night.

_ _ _

... the Real case study

Alma Del Real

... Alma Del Real was never a missing person,

but a victim of homicide that was not being investigated as such

... the less missing, and the less dead

E LaMont Gregory MSc Oxon

... Alma Del Real was never a missing person,

but a victim of homicide that was not being investigated as such

... the less missing, and the less dead

E LaMont Gregory MSc Oxon

Alma Del Real, perished on 12 April 2015

Alma Del Real was 22 years old and weighed some 137 pounds, which was well proportioned on her five-foot-five inch frame.

After a very well attended nearly weeks-long community effort to find Alma Del Real following her disappearance in the wee hours of 12 April, all hope of her eventually being found safe and returned to her home, family and friends came to an end, when her badly-decomposed body was discovered in a culvert in Marshall County, 30 miles south of South Bend, six weeks after she vanished.

She had spent the previous evening with friends at a dance club. A male friend, now the prime person of interest, claimed that he had dropped Alma Del Real off at her home in South Bend. Over the next several weeks, the same male offered police several possible scenarios as to Alma's probable fate, according to South Bend Police Department homicide detectives.

One of those scenarios suggested the involvement of the Latin Kings gang, while another offered by the suspect implied that a cartel had contact with Alma Del Real. There is no indication that alien abduction was put forth as a possible rational explanation.

Only time will tell to what extent the police followed these obfuscations and how they impacted the investigation. But, it seems obvious that they did delay the police from a by-the-numbers investigation, which suggests that the people closest to the victim are the mostly likely suspects. And, it begs credibility as to why the phone records of those who saw her that night were not immediately used to corroborate their statements as to their whereabouts that night. The ping from rural Marshall County should had been known within the first 48 hours of the case.

The prime suspect's statements to police began to unravel, six weeks after the fact, when police compared cell phone location records to where the suspect said he had been after giving Alma a ride to her Ewing Avenue home at about 2am the morning of 12 April.

When police confronted the male friend of the then believed to be missing person with the inconsistencies between where his cell phone use placed him (in Marshall County 30 miles south of South Bend) when he had claimed to be elsewhere. Faced with mounting evidence of his involvement in Alma's disappearance, the suspect then led police to where Alma' remains were in fact found. A location which his cell phone records suggest that he had been in the early morning hours when Alma Del Real supposedly went missing.

Interestingly, a well respected remains location organization based in Texas, had suggested that her body would be found about 20 miles from her home in a rural area within days of her disappearance.

Although this author carries the opinion that the cell record facts could have been known the very first day of Alma's presumed disappearance, with all due respect to the South Bend detectives working the Alma Del Real missing persons (foul play suspected?) case, distinguishing a missing person from a homicide can be rather difficult.

A difficulty, which exists not in the reality of the facts of the case, but in the scant attention paid to the disappearance of a member of the less-missing-less-dead class.

The Alma Del Real case was never a missing persons case, it was a homicide that was not being investigated.

In a nutshell, the problem lies in a culture that drives the administration of the police in South Bend, and neither does it reflect a defect in the skills of individual officers specifically, nor in criminal investigatory science and technique in general.

And therefore, the axiom - when the problem starts at the top, there is no one to tell.

There needs to be a fundamental rethink as to how we approach missing persons investigations.

After a very well attended nearly weeks-long community effort to find Alma Del Real following her disappearance in the wee hours of 12 April, all hope of her eventually being found safe and returned to her home, family and friends came to an end, when her badly-decomposed body was discovered in a culvert in Marshall County, 30 miles south of South Bend, six weeks after she vanished.

She had spent the previous evening with friends at a dance club. A male friend, now the prime person of interest, claimed that he had dropped Alma Del Real off at her home in South Bend. Over the next several weeks, the same male offered police several possible scenarios as to Alma's probable fate, according to South Bend Police Department homicide detectives.

One of those scenarios suggested the involvement of the Latin Kings gang, while another offered by the suspect implied that a cartel had contact with Alma Del Real. There is no indication that alien abduction was put forth as a possible rational explanation.

Only time will tell to what extent the police followed these obfuscations and how they impacted the investigation. But, it seems obvious that they did delay the police from a by-the-numbers investigation, which suggests that the people closest to the victim are the mostly likely suspects. And, it begs credibility as to why the phone records of those who saw her that night were not immediately used to corroborate their statements as to their whereabouts that night. The ping from rural Marshall County should had been known within the first 48 hours of the case.

The prime suspect's statements to police began to unravel, six weeks after the fact, when police compared cell phone location records to where the suspect said he had been after giving Alma a ride to her Ewing Avenue home at about 2am the morning of 12 April.

When police confronted the male friend of the then believed to be missing person with the inconsistencies between where his cell phone use placed him (in Marshall County 30 miles south of South Bend) when he had claimed to be elsewhere. Faced with mounting evidence of his involvement in Alma's disappearance, the suspect then led police to where Alma' remains were in fact found. A location which his cell phone records suggest that he had been in the early morning hours when Alma Del Real supposedly went missing.

Interestingly, a well respected remains location organization based in Texas, had suggested that her body would be found about 20 miles from her home in a rural area within days of her disappearance.

Although this author carries the opinion that the cell record facts could have been known the very first day of Alma's presumed disappearance, with all due respect to the South Bend detectives working the Alma Del Real missing persons (foul play suspected?) case, distinguishing a missing person from a homicide can be rather difficult.

A difficulty, which exists not in the reality of the facts of the case, but in the scant attention paid to the disappearance of a member of the less-missing-less-dead class.

The Alma Del Real case was never a missing persons case, it was a homicide that was not being investigated.

In a nutshell, the problem lies in a culture that drives the administration of the police in South Bend, and neither does it reflect a defect in the skills of individual officers specifically, nor in criminal investigatory science and technique in general.

And therefore, the axiom - when the problem starts at the top, there is no one to tell.

There needs to be a fundamental rethink as to how we approach missing persons investigations.

... to read the entire case study, click on the following URL

https://www.theoxfordscientist.com/where-is-alma-del-real.html

https://www.theoxfordscientist.com/where-is-alma-del-real.html