www.theoxfordscientist.com

- First Duty

- ... the dry cough, a lethal hate crime

- ... open letter to Premier Danielle Smith

- Trump Guilty on all 34 Felony Counts

- shooting of PM of Slovakia

- YouTube channel, launch

- Carlson, tuckered out

- ... Chinese New Year - 2024

- ... orange jesus sprouts sixth finger

- ... Wagner Group in Africa

- ... conduct unbecoming an MP

- Alberta, burning

- ... the Trump legacy

- Eric LaMont Gregory

- Wacko in Waco

- Pence, Christian last

- ... Putin indicted

- The Egyptian Secret

- Fox fiction

- The Open Skies Treaty

- derailed in Ohio

- close your Twitter account

- ... espionage-a-lago

- Highland Park

- Canada bans handguns and assault rifles

- ... apology, only a first step

- ... world wide auto surf

- Conklin to Buffalo

- Danielle Smith and Liz Truss

- An End to War

- Globe & Mail, blatant sophistry

- conservative press, a fitting epitaph

- Uvalde, explanation time

- ... Ukraine, a crime against humanity

- Open Letter to Justin Trudeau

- Queen Elizabeth II

- Moscow Mitch

- ... illiberal roadshow descends on Edmonton

- ... don't cry for Kenney, Alberta

- ... Edmonton, on the world stage

- ... advertise in Chinese & English

- ... missing in Edmonton

- Human Rights

- Facebook, bankrupt ethically & financially

- Pelosi rejects Jordan

- ... vaccine roulette

- ... a mask in time saves nine

- 9/11 + 17

- the Gregory military doctrine

- lying Rodgers, unsportsmanlike Brady, falter

- ... best free traffic list 2021

- 34% of Covid survivors - will not fully recover -

- Trump ... doing Putin's bidding

- Coronavirus, a perfect storm

- Biden/Harris, ... America, can breathe, again

- ... in the heat of the day

- 11 September 2021

- Donald J Trump - like father, like son

- Jim Jordan will resign, inevitably

- ... raise money for your group

- Paris - Sanguinary excess, again

- Mitch McConnell is no Alexander Hamilton

- What Trump knew 28 January 2020

- None Dare Call It Murder

- use of force, part 2

- Coronavirus, the second wave

- Click & Join 2021

- Coronavirus Pandemic, Part 2

- Coronavirus Pandemic

- Terror Returns to London Bridge

- use of force, part 1

- Ohio's trio of shame

- ... how to earn Bitcoin

- Kenney: Scheer nonsense, part 2

- the dark charisma of Donald Trump

- the three stooges

- Trump's base, 24% and dwindling

- Scheer Nonsense

- getting away with murder

- World Wide Auto Surf

- Beyond a reasonable doubt

- Mueller, Redactions & Twitter

- An All Alberta Solution

- Obama Attends Raptors Game

- Call for action on cannabis convictions

- John Bolton: beware the Trojan horse

- Mandel Clarifies MMR Stance

- People First - Dai for Whitemud mp4

- Notley, Mandel or Kenney

- Dai for Whitemud. Dai for Alberta

- To refine or not to refine

- Trump under subpoena

- Mandel vs Elections Alberta

- Individual 1 - Donald J Trump

- Is Mississippi Learning?

- Stand Back & Stand By

- Flynn Seeks Delay in Sentencing

- Roadmap to Trump's Impeachment

- Michael Cohen sentenced

- Trump Obstructing Justice

- Defense Secretary Resigns

- The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Hate Crimes are Increasing

- Trump announces Military Doctrine

- The Meeting, Trump Tower, June 9 2016

- 13 Angry White Male Senators

- Mean SOBs, Ryan & Jordan

- Trumpgate, a review of the facts

- Treason by the Dozens

- Terror on London Bridge

- Anti-Trump Ryan as Speaker, doubtful

- Haiti - shameful Red Cross 40% admin costs

- Deadly Bastille Day in Nice

- Special Powers

- Brussels - revenge attack

- Gregory's forte

- America First

- Brexit triumphs in UK referendum

- Ali

- Guns, Obama, the NRA & the Cleric

- Gorsuch & Brown v Board of Education

- The Generosity of America

- To Protect and To Serve

- Where is Alma Del Real?

- The Islamic World - a primer for policy makers

- The Lists - The Missing and Unsolved Homicides

- Michiana Murders

- Clinton

- Kings, Emperors & John Boehner

- Donnelly - the constant campaigner

- Kevin McCarthy

- Alberta Party

- Selections from The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Malaysian Airlines Flight 370

- Ukraine - the Putin Doctrine

- Twilight

- Principles

- Bridge-gate: a closer look at Christie's staff

- Mandela

- Liangjun Wang

- Rethinking Syria

- about Chechnya

- Rethinking the War on Terror

- Tepid waters

- Linkage Blindness

- None Dare Call it Treason

- Emancipation

- Power

- Newtown - a cry for help

- Quarantine

- 11 September

- Hidden Crimes, Hidden Victims

- Cry, My Beloved Country

- Cruel Winds of October

- Doctrine

- Fed Video

- Under Seige

- Labor Day

- Destiny of America

- McEwen

- Rampage

- Threats

- GSK

- McEwen

- Condoleezza's watch

- Danger

- B R I C S

- Israel

- Huckabee

- Evidence

- Ties that Bind

- Sarajevo / Rwanda

- Violence

- Baby Safety

- MLK

- Libya

- Franklin

- Principles

- Fox 45

- America Wins Nobel Peace Prize

- Celina

- Middletown

- Arms Race

- Egypt

- Dollar

- 3 July

- $6 Trillion

- Jefferson and Adams

- 4th

- Libya

- Fening

- Abe

- Housing for Haiti

- Palin on Haiti

- ' ... an innocent man'

- Oil in the Gulf

- ... a wider regional conflict

- the demise of General McChrystal

- ... and to the republic

- BP and the Precautionary Principle

- Making Sense of Fort Hood

- Air Quality

- Un largo crepúsculo Lucha

- Israel

- Policy

- Home

- Casa

- un tambor diferente

- The Oxford Years

- Defense

- The Secret Hold

- INS will cease to exist

- ABC Toledo

- the grapes of wrath

- H1N1 Fluenza

- Tantamount to Treason

- MKL 4th speech

- Trans Dip

- Trump Rescinds DACA

- Rethinkin Syria

- Oxfam, IRC and other NPR Darlings

- Top Nine Articles for March 2015

- The Ultimate Vanishing Act

- Where is Alma Del Real?

- Alma Del Real

- 11 September

- A Measure of Philanthropic Success

- Tantamount to Treason

- South Carolina

- Double Crossed by Double Standards

- Call for photo radar cash grab inquiry

- Remembrance Day 2015

- Trudeau victory portends

- Blair Speech to Congress 2003

- Justin Trudeau, Tony Blair & Marijuana

- Trump, Harper, Ambrose & Ryan

- Saudi Arabia vs Iran

- The Islamic World ... the basics

- 2020 Presidential Candidate Releases Book

- Mississauga house explosion

- Reset: Driving Black in America

- Giuliani, shut up, stop name calling & prepare to govern

- Stop the Madness in Aleppo & Mosul

- Drain The Swamp

- Unpresidented

- Trump & the CIA, the high priest of false security

- The Hour of Maximum Danger

- Quebec, Queens U, Charleston & Trump

- Paul Ryan, Steve King, Trumpcare & Babies

- Harvey wreaks havoc

- VPN, don't surf without it

- Anju Sharma, the right choice for Edmonton-Mill Woods

- Adlandpro

- Trump's Iranian ties

- Brianna Keilar CNN - the big lie

- ... best free manual surf list 2021

- the Gregory military doctrine

- theOxfordscientist.com now on Tik Tok

- Chopin

- in the Course of human events

- 37 countries ban felon Trump

- un Plat qui se Mange Froid

- Trump shot at rally by 20-year-old

Constitution of the United States

Article I, enumerates the powers and limitations of the legislative branch,

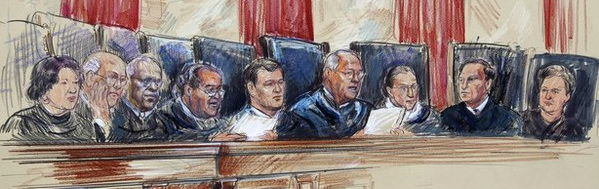

the Supreme Court on Thursday clarified several enumerated powers of the Congress,

which limit the scope of the Commerce, Necessary and Proper, Spending, and its Taxing Powers

940 WCIT Talk Radio - Lima

28 June 2012

3 - 5 pm

Ron Williams - Jeff Hardin - Tom Lucente - Eric LaMont Gregory

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

NATIONAL FEDERATION OF INDEPENDENT BUSINESS ET AL. v.

SEBELIUS, SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 11-393. Argued March 26, 27, 28, 2012 - Decided June 28, 2012*

Syllabus

NATIONAL FEDERATION OF INDEPENDENT BUSINESS ET AL. v.

SEBELIUS, SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 11-393. Argued March 26, 27, 28, 2012 - Decided June 28, 2012*

Hour 1 - Ron Williams, Jeff Hardin, Tom Lucente, Eric LaMont Gregory

Hour 2 - Ron Williams, Sally Pikes*, Tom Lucente, Eric LaMont Gregory

* Sally C Pikes is the author of two books on Obamacare - The truth about Obamacare & The top 10 ways to repeal Obamacare -

* Sally C Pikes is the author of two books on Obamacare - The truth about Obamacare & The top 10 ways to repeal Obamacare -

On Monday morning, the 25th of June 2012, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down three of four contested provisions in Arizona's immigration law and left a fourth provision to future court challenges. There were many who thought that the Arizona ruling portended the end of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, it did not.

The importance of the interpretation of the court as to the Commerce Clause is instructive because it provides substantial protections to individual liberty by drawing a clear distinction between the power to regulate commerce as opposed to the power to compel it. And reaffirms the principle that the Federal Government is a government of limited and enumerated powers, thus

Everyone will likely participate in the markets for food, clothing, transportation, shelter, or energy; that does not authorize Congress to direct them to purchase particular products in those or other markets today. The Commerce Clause is not a general license to regulate an individual from cradle to grave, simply because he will predictably engage in particular transactions. Any police power toregulate individuals as such, as opposed to their activities, remains vested in the States.

Construing the Commerce Clause to permit Congress to regulate individuals precisely because they are doing nothing would open a new and potentially vast domain to congressional authority. Congress already possesses expansive power to regulate what people do. Upholding the Affordable Care Act under the Commerce Clause would give Congress the same license to regulate what people do not do. The Framers knew the difference between doing something and doing nothing. They gave Congress the power to regulate commerce, not to compel it. Ignoring that distinction would undermine the principle that the Federal Government is a government of limited and enumerated powers. The individual mandate thus cannot be sustained under Congress’s power to "regulate Commerce." Pp. 16–27.

The Court also sought to constrain Congress from using the Necessary and Proper Clause to draw those into a regulated status who would otherwise be outside of it by creating the conditions necessary to exercise an enumerated power, thus

Each of this Court’s prior cases upholding laws under that Clause involved exercises of authority derivative of, and in service to, a granted power. E.g., United States v. Comstock, 560 U. S. ___. The individual mandate, by contrast, vests Congress with the extraordinary ability to create the necessary predicate to the exercise of an enumerated power and draw within its regulatory scope those who would otherwise be outside of it. Even if the individual mandate is "necessary" to the Affordable Care Act’s other reforms, such an expansion of federal power is not a "proper" means for making those reforms effective. Pp. 27–30.

In answering a constitutional question, Chief Justice Roberts writes in his opinion, even if it is necessary to disregard the fact that in the Act the "[s]hared responsibility payment" was called a "penalty," and whereas, that label is fatal to the application of the Anti-Injunction Act. It is true that Congress cannot change whether an exaction is a tax or a penalty for constitutional purposes simply by describing it as one or the other. The functional approach to judicial interpretation suggests that nomenclature alone does not, however, control whether an exaction is within Congress’s power to tax.

This author argued for the last two years that in part the Court would cite a number of previous mandates including the mandate to purchase firearms in anticipation of militia service, the Militia Act of 1792, one of the first acts of our newly formed Congress, which should the Court so choose could be integral in any decision of the Affordable Care Act's constitutionality. A lot more attention should be paid to the 1792 act by those who want to protect their Second Amendment rights, thus

The examples of other congressional mandates cited by Justice Ginsburg, post, at 35, n. 10 (opinion concurring in part, concurring in judgment in part, and dissenting in part), are not to the contrary. Each of those mandates—to report for jury duty, to register for the draft, to purchase firearms in anticipation of militia service, to exchange gold currency for paper currency, and to file a tax return—are based on constitutional provisions other than the Commerce Clause. See Art. I, §8, cl. 9 (to "constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court"); id., cl. 12 (to "raise and support Armies"); id., cl. 16 (to "provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia"); id., cl. 5 (to "coin Money"); id., cl. 1 (to "lay and collect Taxes").

The precise wording when interpreting the constitution is important but, the practical operation of the law not any magic words is the essential consideration when determining a laws constitutionality. Therefore, the use of the word penalty in the Act does not alter the fact that the function of the penalty serves the same function that a tax serves, thus

We thus ask whether the shared responsibility payment falls within Congress’s taxing power, "[d]isregarding the designation of the exaction, and viewing its substance and application." United States v. Constantine, 296 U. S. 287, 294 (1935); cf. Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U. S. 298, 310 (1992) ("[M]agic words or labels" should not "disable an otherwise constitutional levy"; Nelson v. Sears Roebuck & Co., 312 U. S. 359, 363 (1941) ("In passing on the constitutionality of a tax law, we are concerned only with its practical operation, not its definition or the precise form of descriptive words which may be applied to it."

The same analysis here suggests that the shared responsibility payment may for constitutional purposes be considered a tax, not a penalty: First, for most Americans the amount due will be far less than the price of insurance, and, by statute, it can never be more.*

* In 2016, for example, individuals making $35,000 a year are expected to owe the IRS about $60 for any month in which they do not have health insurance. Someone with an annual income of $100,000 a year would likely owe about $200 for any month in which they do not have health insurance.

It is estimated that four million people each year will choose to pay the IRS rather than buy insurance. See Congressional Budget Office, supra, at 71. We would expect Congress to be troubled by that prospect if such conduct were unlawful. That Congress apparently regards such extensive failure to comply with the mandate as tolerable suggests that Congress did not think it was creating four million outlaws. It suggests instead that theshared responsibility payment merely imposes a tax citizens may lawfully choose to pay in lieu of buying health insurance.

The payment is also plainly not a tax on the ownership of land or personal property. The shared responsibility payment is thus not a direct tax that must be apportioned among the several States.

If it is troubling to interpret the Commerce Clause as authorizing Congress to regulate those who abstain from commerce, perhaps it should be similarly troubling to permit Congress to impose a tax for not doing something.

Three considerations allay this concern. First, and most importantly, it is abundantly clear the Constitution does not guarantee that individuals may avoid taxation through inactivity. A capitation, after all, is a tax that everyone must pay simply for existing, and capitations are expressly contemplated by the Constitution. The Court today holds that our Constitution protects us from federal regulation under the Commerce Clause so long as we abstain from the regulated activity. But from its creation, the Constitution has made no such promise with respect to taxes. See Letter from Benjamin Franklin to M. Le Roy (Nov. 13, 1789) ("Our new Constitution is now established . . . but in this world nothing can be said to be certain,except death and taxes").

Sustaining the mandate as a tax depends only on whether Congress has properly exercised its taxing power to encourage purchasing health insurance, not whether it can.

Individuals do not have a lawful choice not to pay a taxdue, and may sometimes face prosecution for failing to do so (although not

for declining to make the shared responsibility payment, see 26 U. S. C. §5000A(g)(2)). But that does not show that the tax restricts the lawful choice whether to undertake or forgo the activity on which the taxis predicated. Those subject to the individual mandate may lawfully forgo health insurance and pay higher taxes, or buy health insurance and pay lower taxes. The only thing they may not lawfully do is not buy health insurance and not pay the resulting tax.

The Federal Government does not have the power toorder people to buy health insurance. Section 5000A would therefore be unconstitutional if read as a command. The Federal Government does have the power to impose atax on those without health insurance. Section 5000A is therefore constitutional, because it can reasonably be read as a tax.

In our system of constitutional limited government, when all else is said and done, it is the people who decide ultimately. And, that is where responsibility began in our Republic, and where it resides today. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves ...

Members of this Court are vested with the authority to interpret the law; we possess neither the expertise nor the prerogative to make policy judgments. Those decisions are entrusted to our Nation’s elected leaders, who can be thrown out of office if the people disagree with them. It is not our job to protect the people from the consequences of their political choices.

We thus ask whether the shared responsibility payment falls within Congress’s taxing power, "[d]isregarding the designation of the exaction, and viewing its substance and application." United States v. Constantine, 296 U. S. 287, 294 (1935); cf. Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U. S. 298, 310 (1992) ("[M]agic words or labels" should not "disable an otherwise constitutional levy"; Nelson v. Sears Roebuck & Co., 312 U. S. 359, 363 (1941) ("In passing on the constitutionality of a tax law, we are concerned only with its practical operation, not its definition or the precise form of descriptive words which may be applied to it."

The same analysis here suggests that the shared responsibility payment may for constitutional purposes be considered a tax, not a penalty: First, for most Americans the amount due will be far less than the price of insurance, and, by statute, it can never be more.*

* In 2016, for example, individuals making $35,000 a year are expected to owe the IRS about $60 for any month in which they do not have health insurance. Someone with an annual income of $100,000 a year would likely owe about $200 for any month in which they do not have health insurance.

It is estimated that four million people each year will choose to pay the IRS rather than buy insurance. See Congressional Budget Office, supra, at 71. We would expect Congress to be troubled by that prospect if such conduct were unlawful. That Congress apparently regards such extensive failure to comply with the mandate as tolerable suggests that Congress did not think it was creating four million outlaws. It suggests instead that theshared responsibility payment merely imposes a tax citizens may lawfully choose to pay in lieu of buying health insurance.

The payment is also plainly not a tax on the ownership of land or personal property. The shared responsibility payment is thus not a direct tax that must be apportioned among the several States.

If it is troubling to interpret the Commerce Clause as authorizing Congress to regulate those who abstain from commerce, perhaps it should be similarly troubling to permit Congress to impose a tax for not doing something.

Three considerations allay this concern. First, and most importantly, it is abundantly clear the Constitution does not guarantee that individuals may avoid taxation through inactivity. A capitation, after all, is a tax that everyone must pay simply for existing, and capitations are expressly contemplated by the Constitution. The Court today holds that our Constitution protects us from federal regulation under the Commerce Clause so long as we abstain from the regulated activity. But from its creation, the Constitution has made no such promise with respect to taxes. See Letter from Benjamin Franklin to M. Le Roy (Nov. 13, 1789) ("Our new Constitution is now established . . . but in this world nothing can be said to be certain,except death and taxes").

Sustaining the mandate as a tax depends only on whether Congress has properly exercised its taxing power to encourage purchasing health insurance, not whether it can.

Individuals do not have a lawful choice not to pay a taxdue, and may sometimes face prosecution for failing to do so (although not

for declining to make the shared responsibility payment, see 26 U. S. C. §5000A(g)(2)). But that does not show that the tax restricts the lawful choice whether to undertake or forgo the activity on which the taxis predicated. Those subject to the individual mandate may lawfully forgo health insurance and pay higher taxes, or buy health insurance and pay lower taxes. The only thing they may not lawfully do is not buy health insurance and not pay the resulting tax.

The Federal Government does not have the power toorder people to buy health insurance. Section 5000A would therefore be unconstitutional if read as a command. The Federal Government does have the power to impose atax on those without health insurance. Section 5000A is therefore constitutional, because it can reasonably be read as a tax.

In our system of constitutional limited government, when all else is said and done, it is the people who decide ultimately. And, that is where responsibility began in our Republic, and where it resides today. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves ...

Members of this Court are vested with the authority to interpret the law; we possess neither the expertise nor the prerogative to make policy judgments. Those decisions are entrusted to our Nation’s elected leaders, who can be thrown out of office if the people disagree with them. It is not our job to protect the people from the consequences of their political choices.

In final analysis, Cief Justice Roberts agreed with the other conservative members of the court that the Commerce Clause did

not justify the individual mandate. He also voted with the conservatives to say the Necessary and Proper Clause did not justify the mandate, and to limit the federal government’s power to force states to carry out the planned expansion of Medicaid.

The chief justice broke with the conservatives in finding that the mandate's penalty for not buying health insurance was a - tax -and although that finding is extremely important for the future of the Affordable Care Act, is does not answer any consequential legal questions, as does the court's stance on the Commerce and Necessary and Proper Clause rulings.

not justify the individual mandate. He also voted with the conservatives to say the Necessary and Proper Clause did not justify the mandate, and to limit the federal government’s power to force states to carry out the planned expansion of Medicaid.

The chief justice broke with the conservatives in finding that the mandate's penalty for not buying health insurance was a - tax -and although that finding is extremely important for the future of the Affordable Care Act, is does not answer any consequential legal questions, as does the court's stance on the Commerce and Necessary and Proper Clause rulings.